Gentle Theorems: Difference of Squares

I have a (not very controversial) feeling that people don’t feel as though algebra is actually a thing you can use for stuff. I fall into this trap myself often, despite being someone who does math for a living, and so I suspect this is a pretty wide-spread phenomenon. Let me explain.

For example, consider the equation:

\[ (x + y)(x - y) = x^2 - y^2 \]

This is known as the difference of squares. Let’s work through the derivation of it together:

\[ \begin{align*} (x + y)(x - y) &= (x + y)(x - y) \\ &= x^2 + xy - xy - y^2 \\ &= x^2 + \cancel{xy - xy} - y^2 \\ &= x^2 - y^2 \end{align*} \]

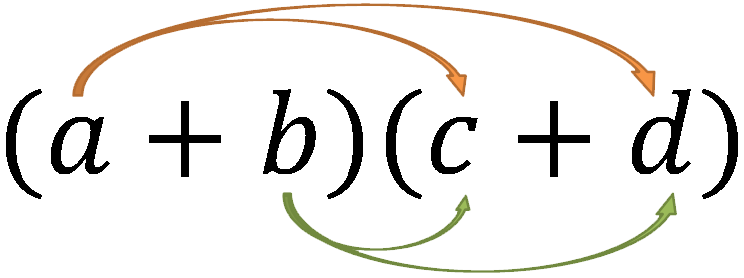

Recall that we can use the FOIL method to get from the first line to the second.

I implore you to read through this proof carefully, and convince yourself of its truthfulness – even if you don’t consider yourself a “math” person. Believe it or not, there’s a point I’m getting to.

Anyway – by all accounts, this difference of squares thing is a pretty humdrum theorem. Who really cares, right? Let’s switch gears for a bit and talk about something more interesting.

Recall that \(20 \times 20 = 400\). As an interesting question, without actually computing it, let’s think about the product \(19 \times 21\). What does this equal? It seems like it could also be \(400\) – after all, all we did was take one away from the left side of the times and move it to the right.

In fact, if you work it out, \(19 \times 21 = 399\). That’s kind of interesting: somehow we lost a \(1\) by shuffling around the things we were multiplying.

This seems to not be an isolated incident:

\[ \begin{align*} 5 \times 5 &= 25 \\ \text{but,}\quad4 \times 6 &= 24 \end{align*} \]

\[ \begin{align*} 10 \times 10 &= 100 \\ \text{but,}\quad9 \times 11 &= 99 \end{align*} \]

An intriguing question to ask yourself is whether this is always true, or whether we’ve just gotten lucky with the examples we looked at.

But the more interesting question, in my opinion, is what happens if we go from \(19 \times 21 = 399\) to \(18\times22\). Will we lose another \(1\) when we fiddle with it? Or will something else happen? Form an opinion on what the answer will be before continuing.

\[ \begin{align*} 20 \times 20 &= 400 \\ \text{but,}\quad 21 \times 19 &= 399 \\ \text{but,}\quad 22 \times 18 &= 396 \end{align*} \]

Weird – somehow we lost \(3\) that time. What’s happened here?

If you’re confused (and I was, when I first saw this), don’t despair. As it happens, you already know the answer!

So, what’s going on here? Well, we’ve actually just been dealing with differences of squares the whole time – probably without even realizing it!

Most people, I think, fail to connect the algebraic fact that \((x+y)(x-y)=x^2-y^2\) to the fact that \(22\times18=396\). If you still don’t see why, we can explicitly fill in our variables:

\[ \begin{align*} 22\times18&=(20+2)(20-2)\\ &=20^2-2^2 \\ &= 400 - 4 \\ &= 396 \end{align*} \]

Neat, right? Even if you carefully read through the proof of the difference of squares earlier, you might not have noticed that we’ve been playing with them the entire time! I blame western math education for this; too often are equations presented only to be solved, and never to be thought about. It’s a disservice we’ve done to ourselves.

The takeaway of all of this, in my opinion, is that we should spend some time thinking about the notion of equality, about the \(=\) symbol. Ever since looking at this difference of squares thing, I’ve started viewing \(=\) not as the symbol which separates the left side of an equation from the right, but as a transformation. The \(=\) sign transforms something we can experience into something we can manipulate, and back again.

What I mean by that is that it’s a lot easier to conceptualize \(22\times18\) than it is to think about \((x+y)(x-y)\). The numeric representation is better suited for human minds to experience, while the algebraic expression is better at twiddling. We know how to twiddle algebra, but twiddling numbers themselves is rather meaningless.

In terms of everyday usefulness, this isn’t particularly helpful, except that it’s often easier to compute a difference of squares than it is to do the multiplication naively. If you can recognize one, you could probably impress someone with your mental arithmetic – but, again, it’s not going to revolutionize your life in any way.

All of this is to say that math is neat. Even if you don’t see any practical value in this stuff, hopefully you’ll agree that there might be interesting puzzles to be found here. And, as it turns out, algebra can be a satisfying tool for solving these puzzles.

Thanks to Matt Parsons for proof-reading an early version of this post.