Preface

How These Things Work: The Preface

Table of Contents

Part 1 – Diagrams

- Preface

- Machine Diagrams

- Universal Machines

- Interlude

- Numbers

- Arithmetic

- Abstraction

- Multiplexing

- Latches

- Constructions on Annotations

- Memory Cells

Part 2 – Symbolic Computations

- A New Foundation

- Symbolic Computation

- Symbolic Evaluation and Equational Reasoning

- More Types

- Polymorphism

- Back in Business and Better than Ever

- The Infectiousness of Reality

- Functions

- Kleisli Categories

- Revisiting State

- Kleisli Tools

Part 3

Preface

The last decade of my life has been marked by acquiring knowledge around computers – how they work, and, more interestingly, why they work. Ostensibly this pursuit is known as computer science, but my most profound realization over the previous ten years is that computer science has as much to do with computers as it does with snowmen. That is to say, not much.

A few years ago, I asked my engineer friend about how much of civilization he could rebuild singlehandedly, should he survive some hypothetical apocalyptic event. “All of it,” he replied. “Not all at once, but I know enough to be able to puzzle together the pieces I don’t know right this second.”

That sentiment strongly resounded with me, and I’ve been thinking about it ever since. I share my friend’s optimism, that given enough large pieces of the puzzle, it’s possible to work backwards and figure out what shapes must have filled the gaps. It’s likely not an overnight endeavor, but it’s doable.

And so that’s what this book strives to be: my contribution to any hypothetical survivors of the hypothetical apocalypse. A gentle, yet comprehensive introduction to how these things work. It won’t answer every question you might have, but the motivated reader will learn enough to be able to answer the remaining questions themselves.

“But what of the rest of us,” you might be wondering. “Does this book hold any value for those of us without the delusions of grandeur to think we can rebuild civilization?” Perhaps I am biased, but I think it does, yes.

While computer science has very little to do with snowmen, it has everything to do with patterns. The study of computer science, like mathematics, is one of overwhelming self-referentiality. The patterns that seemed so difficult and novel yesterday are today’s run-of-the-mill building blocks. Like a snowball rolling down a mountain, the student of computer science cannot help but gain momentum as these concepts begin converge in one huge avalanche.

This process of using tools you built yesterday to help build bigger tools today is called abstraction, and it is the most powerful force I know of in the universe. Abstraction is the process of standing on the shoulders of giants, and using them to reach new heights. In my opinion, abstraction is the only reason humanity has managed to crawl its way out of the savannas and into something exceptionally worthwhile.

Computer science is how I learned to do abstraction, and it is my most enrichingly- and economically- valuable skill. This is the final reason I offer to you why these things might be worth learning: it is strongly likely that you will make more money with them than without. As we will later see, abstraction is literally impossible to automate in the general case. This makes it a compelling skill to have in a world rapidly driving towards automating away most jobs. The debate whether or not that’s a good thing is left to minds smarter than my own, but you have to admit that it’s nice to have options.

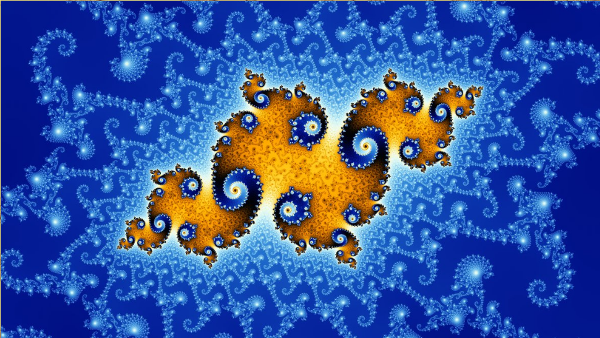

The attentive reader will notice a theme throughout this book. Like a fractal, we will same patterns reoccurring in deeper and deeper shades of abstraction, and as we learn more, our tools will begin to work on many different levels simultaneously. There are two marvelous experiences here – the amazement that such things can keep happening – and, in the later chapters, the eventual understanding behind why.

Finally, I’d like to dedicate this book to my mum, whose thirst for knowledge has always inspired me, and to my father, who gave me this mindset in the first place.