Nimic: A language about nothing

If you haven’t heard, I recently solicited couches to stay on. The idea is to cruise around the globe, meeting cool programmers, and collaborating with them on whatever project they’re most excited about.

This weekend I spent time with the inimitable David Rusu. The bar for my trip has been set extremely high; not only is David an amazing host, but we hashed out a particularly interesting project in a couple of days. We call it nimic.

Nimic is a free-form macro language, without any real syntax, or operational semantics. We have a super bare bones parser that groups parenthetical expressions, and otherwise admits any tokens, separated by whitespace. The language will attempt to run each of its macros on the deepest, leftmost part of this grouping structure. If nothing matches, the program is stuck and we just leave it.

Therefore, hello world in nimic is just the stuck program:

hello worldwhich you have to admit is about as small as you can get it. The core language installs four built-in macros; the most interesting of which is macro — allowing you to define new macros. The syntax is macro pattern rewrite, which itself will be rewritten as the stuck term defined.

As a first program, we can use macro to rewrite the defined term:

macro defined (nimic is weird)which will step to defined via the definition of macro, and then step to nimic is weird via the new defined rule. Here it gets stuck and does no more work.

You can use the special tokens #foo to perform pattern matching in a macro. These forms are available in the rewrite rule. For example,

macro (nimic is #adjective) (nimic is very #adjective)will replace our nimic is weird term with nimic is very weird. You can bind as many subterms in a macro as you’d like.

Because nimic attempts to run all of its macros on the deepest, leftmost part of the tree it can, we can exploit this fact to create statements. Consider the program:

(macro (#a ; #b) #b)

; ( (macro (what is happening?) magic)

; (what is happening?)

)Here we’ve built a cons list of the form (head ; tail). Our default evaluation order will dive into the leftmost leaf of this tree, and evaluate the (macro (#a ; #b) #b) term there, replacing it with defined. Our tree now looks like this:

(defined

; ( (macro (what is happening?) magic)

; (what is happening?)

)where our new #a : #b rule now matches, binding #a to defined, and #b to the tail of this cons cell. This rule will drop the defined, and give us the new tree:

( (macro (what is happening?) magic)

; (what is happening?)

)whereby we now can match on the leftmost macro again. After a few more steps, our program gets stuck with the term magic. We’ve defined sequential evaluation!

But writing cons cells by hand is tedious. This brings us to the second of our built-in macros, which is rassoc #prec #symbol. The evaluation of this will also result in defined, but modifies the parser so that it will make #symbol be right-associative with precedence #prec. As a result, we can use rassoc 1 ; to modify the parser in order to turn a ; b ; c into a ; (b ; (c)).

Therefore, the following program will correctly get stuck on the term finished:

(macro (#a ; #b) #b)

; ((rassoc 1 ;)

;

( this is now

; parsed correctly as a cons cell

; finished

)))The final primitive macro defined in nimic is bash #cmd, which evaluates #cmd in bash, and replaces itself with the resulting output. To illustrate, the following program is another way of writing hello world:

bash (echo "hellozworld" | tr "z" " ")Note that the bash command isn’t doing any sort of bash parsing here. It just takes the symbols echo "hellozworld" | tr "z" " and ", and dumps them out pretty printed into bash. There are no string literals.

We can use the bash command to do more interesting things. For example, we can use it to define an import statement:

macro (import #file) (bash (cat #file))which when you evaluate import some/file.nim, will be replaced with (bash (cat some/file.nim)), which in turn with the contents of some/file.nim. You have to admit, there’s something appealing about even the module system being defined in library code.

But we can go further. We can push our math runtime into bash!

macro (math #m) (bash (bc <<< " #m "))which will correctly evaluate any math expressions you shoot its way.

Personally, I’m not a big fan of the macro #a #b notation. So instead I defined my own sequent notation:

rassoc 2 ----------

; macro (#a ---------- #b) (macro #a #b)This thing defines a macro, which, when expanded, will itself define a macro. Now David and I don’t need to have any discussions bikeshedding over syntax. We can just define whatever we want!

For a longer example, I wanted to implement pattern matching a la Haskell.

My first step was to define a lazy if statement. Because macros are tried most-recently-defined first, I can define my operational semantics first. The rule is to force the condition:

; if #cond then #a else #b

----------

if !#cond then #a else #b(the exclamation marks here are magic inside of the macro macro, which will force macro expansion at whatever it’s attached to) Next, I give two more expansion rules for what to do if my condition is true and false:

; if True then #a else #b

----------

#a

; if False then #a else #b

----------

#bGreat! We can define syntactic equality of stuck terms by forcing two subterms, and then checking them in bash for string equality:

; judge #a #b

----------

is zero !(bash ([[ " !#a " == " !#b " ]]; echo $?))

; is zero #n

----------

False

; is zero 0

----------

TrueWe can try this out. judge hello hello and judge (macro (a a a) b) defined both step to True, but judge foo bar steps to False.

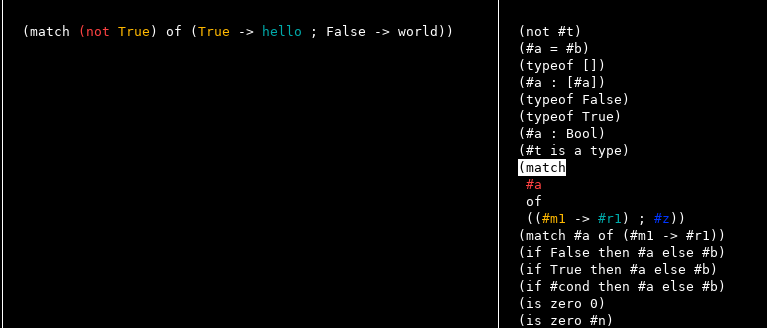

Finally, we’re ready to define pattern matching. We start with the base case in which there is only one pattern we can match on:

; match #a of (#m1 -> #r1)

----------

if !(judge #a #m1) then #r1 else (failed match)We replace our match statement with an equality test, and produce failed match if the two things aren’t identical.

There’s also an induction case, where we want to match on several possibilities.

; match #a of (#m1 -> #r1 ; #z)

----------

if !(judge #a #m1) then #r1 else (match !#a of #z)Here we’d like to perform the same rewrite, but the else case should pop off the failed match.

Amazingly, this all just works. Let’s try it:

; rassoc 3 =

; #a = #b

----------

#a

----------

#b

; not #t =

match #t of

( True -> False

; False -> True

)

; match (not True) of

( True -> hello

; False -> it works!

)This program will get stuck at it works!. Pretty sweet!

The core nimic implementation is 420 lines of Haskell code, including a hand-rolled parser and macro engine. But wait, there’s more! There’s also an additional 291 line interactive debugger, which allows you to step through the macro expansion of your program. It’s even smart enough to colorize the variables in your source tree that are being matched by the current macro.

Not bad for a weekend of work. I can barely contain my excitement for what other cool projects are on the horizon.