Devlog: Navigation

One of the tropes of the golden era of point-n-click adventure games is, would you believe it, the pointing and clicking. In particular, pointing where you’d like the avatar to go, and clicking to make it happen. This post will explore how I made that happen in my neptune game engine.

The first thing we need to do is indicate to the game which parts of the background should be walkable. Like we did for marking hotspots, we’ll use an image mask. Since we have way more density in an image than we’ll need for this, we’ll overlay it on the hotspot mask.

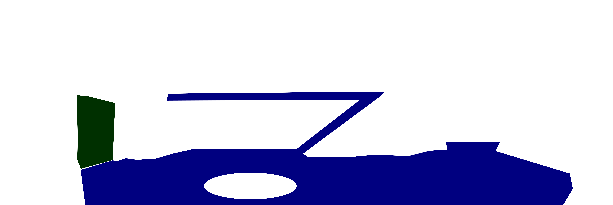

Again, if the room looks like this:

Our mask image would look like this:

Here, the walkable section of the image is colored in blue. You’ll notice there’s a hole in the walk mask corresponding to the table in the room; we wouldn’t want our avatar to find a path that causes him to walk through the table.

However there is something important to pay attention to here; namely that we’re making an adventure game. Which is to say that our navigation system doesn’t need to be all that good; progress in the game is blocked more by storytelling and puzzles than it is by the physical location of the player (unlike, for example, in a platformer game.) If the avatar does some unnatural movement as he navigates, it might be immersion-breaking, but it’s not going to be game-breaking.

Which means we can half ass it, if we need to. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

The first thing we’re going to need is a function which samples our image mask and determines if a given position is walkable.

canWalkOn :: Image PixelRGBA8 -> V2 Int -> Bool

canWalkOn img (V2 x y)

= flip testBit walkableBit

. getWalkableByte

$ pixelAt img x y

where

getWalkableByte (PixelRGBA8 _ _ b _) = b

walkableBit = 7Currying this function against our image mask gives us a plain ol’ function which we can use to query walk-space.

In a 3D game, you’d use an actual mesh to mark the walkable regions, rather than using this mask thing. For that purpose, from here on out we’ll call this thing a navmesh, even though it isn’t strictly an appropriate name in our case.

Because pathfinding algorithms are defined in terms of graphs, the next step is to convert our navmesh into a graph. There are lots of clever ways to do this, but remember, we’re half-assing it. So instead we’re going to do something stupid and construct a square graph by sampling every \(n\) pixels, and connecting it to its orthogonal neighbors if both the sample point and its neighbor are walkable.

It looks like this:

Given the navmesh, we sample every \(n\) points, and determine whether or not to put a graph vertex there (white squares are vertices, the black squares are just places we sampled.) Then, we put an edge between every neighboring vertex (the white lines.)

We’re going to want to run A* over this graph eventually, which is implemented in Haskell via Data.Graph.AStar.aStar. This package uses an implicit representation of this graph rather than taking in a graph data structure, so we’ll construct our graph in a manner suitable for aStar.

But first, let’s write some helper functions to ensure we don’t get confused about whether we’re in world space or navigation space.

-- | Sample every n pixels in on the navmesh.

sampleRate :: Float

sampleRate = 4

-- | Newtype to differentiate nav node coordinates from world coordinates.

newtype Nav = Nav { unNav :: Int }

deriving (Eq, Ord, Num, Integral, Real)

toNav :: V2 Float -> V2 Nav

toNav = fmap round

. fmap (/ sampleRate)

fromNav :: V2 Nav -> V2 Float

fromNav = fmap (* sampleRate)

. fmap fromIntegraltoNav and fromNav are roughly inverses of one another – good enough for half-assing it at least. We’ll do all of our graph traversal stuff in nav-space, and use world-space only at the boundaries.

We start with some helper functions:

navBounds :: Image a -> V2 Nav

navBounds = subtract 1

. toNav

. fmap fromIntegral

. imageSizenavBound gives us the largest valid navigation point from an image – this will be useful later when we want to build a graph and don’t want to sample points that are not on it.

The next step is our neighbors function, which should compute the edges for a given node on the navigation step.

neighbors :: Image PixelRGBA8 -> V2 Nav -> HashSet (V2 Nav)

neighbors img v2 = HS.fromList $ do

let canWalkOn' = canWalkOn img

. fmap floor

. fmap fromNav

V2 x y <- fmap (v2 &)

[ _x -~ 1

, _x +~ 1

, _y -~ 1

, _y +~ 1

]

guard $ canWalkOn' v2

guard $ x >= 0

guard $ x <= w

guard $ y >= 0

guard $ y <= h

guard . canWalkOn' $ V2 x y

return $ V2 x yWe use the list monad here to construct all of the possible neighbors – those which are left, right, above and below our current location, respectively. We then guard on each, ensure our current nav point is walkable, that our candidate neighbor is within nav bounds, and finally that the candidate itself is walkable. We need to do this walkable check last, since everything will explode if we try to sample a pixel that is not in the image.

Aside: if you actually have a mesh (or correspondingly a polygon in 2D), you can bypass all of this sampling nonsense by tessellating the mesh into triangles, and using the results as your graph. In my case I didn’t have a polygon, and I didn’t want to write a tessellating algorithm, so I went with this route instead.

Finally we need a distance function, which we will use both for our astar heuristic as well as our actual distance. The actual distance metric we use doesn’t matter, so long as it corresponds monotonically with the actual distance. We’ll use distance squared, because it has this monotonic property we want, and saves us from having to pay the cost of computing square roots.

distSqr :: V2 Nav -> V2 Nav -> Float

distSqr x y = qd (fmap fromIntegral x) (fmap fromIntegral y)And with that, we’re all set! We can implement our pathfinding by filling in all of the parameters to aStar:

pathfind :: Image PixelRGBA8 -> V2 Float -> V2 Float -> Maybe [V2 Float]

pathfind img = \src dst ->

fmap fromNav <$> aStar neighbors distSqr (distSqr navDst) navSrc

where

navSrc = toNav src

navDst = toNav dstSweet. We can run it, and we’ll get a path that looks like this:

Technically correct, in that it does in fact get from our source location to our destination. But it’s obviously half-assed. This isn’t the path that a living entity would take; as a general principle we try not to move in rectangles if we can help it.

We can improve on this path by attempting to shorten it. In general this is a hard problem, but we can solve that by giving it the old college try.

Our algorithm to attempt to shorten will be a classic divide and conquer approach – pick the two endpoints of your current path, and see if there is a straight line between the two that is walkable throughout its length. If so, replace the path with the line you just constructed. If not, subdivide your path in two, and attempt to shorten each half of it.

Before we actually get into the nuts and bolts of it, here’s a quick animation of how it works. The yellow circles are the current endpoints of the path being considered, and the yellow lines are the potential shortened routes. Whenever we can construct a yellow line that doesn’t leave the walkable region, we replace the path between the yellow circles with the line.

The “divide and conquer” bit of our algorithm is easy to write. We turn our path list into a Vector so we can randomly access it, and then call out to a helper function sweepWalkable to do the nitty gritty stuff. We append the src and dst to the extrema of the constructed vector because aStar won’t return our starting point in its found path, and because we quantized the dst when we did the pathfinding, so the last node on the path is the closest navpoint, rather than being where we asked the character to move to.

shorten :: Image PixelRGBA8 -> V2 Float -> V2 Float -> [V2 Float] -> [V2 Float]

shorten img src dst path =

let v = V.fromList $ (src : path) ++ [dst]

in go 0 (V.length v - 1) v

where

go l u v =

if sweepWalkable img (v V.! l) (v V.! u)

then [v V.! u]

else let mid = ((u - l) `div` 2) + l

in go l mid v ++ go mid u vThe final step, then, is to figure out what this sweepWalkable thing is. Obviously it wants to construct a potential line between its endpoints, but we don’t want to have to sample every damn pixel. Remember, we’re half-assing it. Instead, we can construct a line, but actually only sample the nav points that are closest to it.

In effect this is “rasterizing” our line from its vector representation into its pixel representation.

Using the Pythagorean theorem in navigation space will give us the “length” of our line in navigation space, which corresponds to the number of navpoints we’ll need to sample.

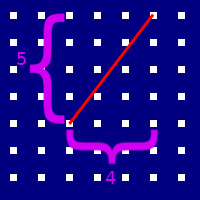

For example, if our line looks like this:

Then the number \(n\) of nav points we need to sample is:

\[ \begin{align*} n &= \lfloor \sqrt{4^2 + 5^2} \rfloor \\ &= \lfloor \sqrt{16 + 25} \rfloor \\ &= \lfloor \sqrt{41} \rfloor \\ &= \lfloor 6.4 \rfloor \\ &= 6 \end{align*} \]

We can then subdivide our line into 6 segments, and find the point on the grid that is closest to the end of each. These points correspond with the nodes that need to be walkable individually in order for our line itself to be walkable. This approach will fail for tiny strands of unwalkable terrain that slices through otherwise walkable regions, but maybe just don’t do that? Remember, all we want is for it to be good enough – half-assing it and all.

So, how do we do it?

sweepWalkable :: Image PixelRGBA8 -> V2 Float -> V2 Float -> Bool

sweepWalkable img src dst =

let dir = normalize $ dst - src

distInNavUnits = round $ distance src dst

bounds = navBounds img

in getAll . flip foldMap [0 .. distInNavUnits] $ \n ->

let me = src + dir ^* (fromIntegral @Int n)

in All . canWalkOn' img

. clamp (V2 0 0) bounds

$ toNav meSweet! Works great! Our final pathfinding function is thus:

navigate :: Image PixelRGBA8 -> V2 Float -> V2 Float -> Maybe [V2 Float]

navigate img src dst = fmap (shorten img src dst) $ pathfind src dstGolden, baby.

Next time we’ll talk about embedding a scripting language into our game so we don’t need to wait an eternity for GHC to recompile everything whenever we want to change a line of dialog. Until then!